Mariana Barragan

Alicia Odewale greets the audience at the President’s Lecture Series: "Searching for Black Ancestors in the American West."

On Feb. 18, Alicia Odewale delivered a lecture on ‘Searching for Black Ancestors in the American West’ in the TDECU Tour Room as part of the President’s Lecture Series in celebration of Black History Month.

Odewale is an African diaspora archaeologist whose research focuses on the Caribbean and southeastern United States. She reanalyzes historical evidence using radical mapping techniques.

In 2016, she made history as the first Black person to receive a doctoral degree in anthropology from the University of Tulsa and subsequently became the first Black faculty member to join the university’s anthropology department.

Odewale has received multiple awards, including those from the National Geographic Society, the American Anthropological Association, and the National Science Foundation. Her work extends to teaching through the National Geographic Explorer classroom at Rice University and, most recently, at the University of Houston, where she teaches two new courses: “Before Cowboy Carter: Black Towns, Black Freedom” and “Finding Black Ancestors.”

“What does it mean to be a good descendant? What do we owe the people who came before us?” Odewale asked towards the end of her presentation. “For me, it means finding everything my ancestors left for me, wherever it exists in the world, however I can find it. And I hope you take on that charge as well.”

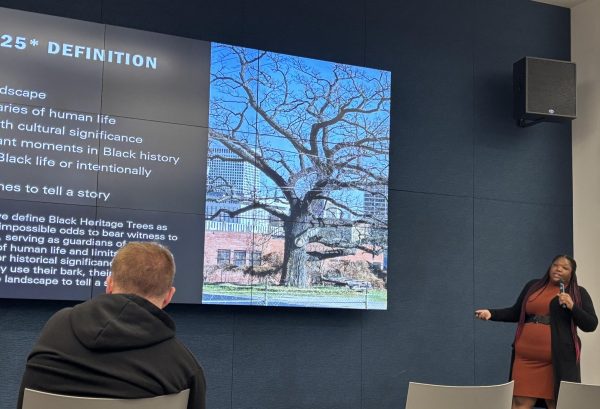

Dr. Odewale introduces the concept of heritage trees based on her latest research, The Black Heritage Tree Project, sponsored by the National Geographic Society. Credit: Mariana Barragan

With that sentiment in mind, Odewale’s lecture aimed to answer the question, “How do we use archaeology as a tool to find Black ancestors in the American West?” She engaged her audience with true or false questions, encouraging participation in the conversation about how, when, where, and what to use from archaeology to answer this question, fostering a safe environment for exploration.

“All of this work uses archaeology as a tool to help Black communities around the world heal from historical trauma. That is the goal,” Odewale said.

While discussing archives such as oral histories, narratives, maps, photographs, buildings, artifacts and the concept of heritage trees (spirit trees, survivor trees, witness trees), she enlightened her audience of the fact that no single tool, website, platform or methodology will ever be enough to find one’s ancestors.

To find them, one needs to go beyond the mainstream narrative, out of the margins, and layer sources to paint a clearer picture. The methods for searching need to be as diverse as the pathways to Black freedom were.

“We have a lot of power in archaeology that can be used to find certain things, but it depends on who is wielding it,” Odewale concluded. “When you are a Black archaeologist, you ask different questions, use different tools, and have different methods in mind… So, a lot of these things I am talking about are not new, but they are in new hands.”

This was the first installment of this spring semester’s President’s Lecture Series, which aims to bring thought-provoking content from informed guests to spark both conversation and inquiry.