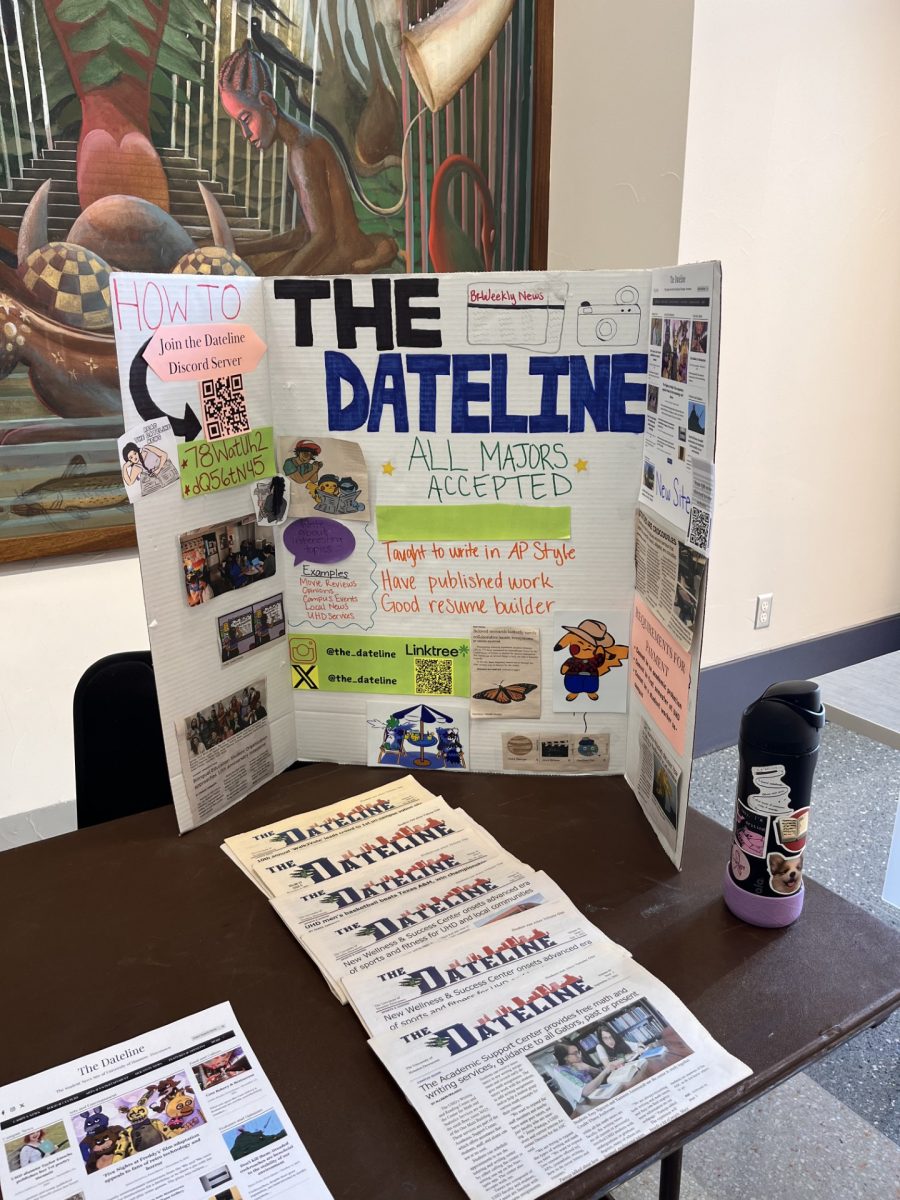

The Contemporary Arts Museum Houston’s current exhibit contains an accumulation of Vincent Valdez’s career spanning 25 years. It is the first time ever that the museum dedicates its entire museum to one artist.

According to CAMH curator Patricia Restrepo, this decision demonstrates the museum’s commitment to Valdez’s talent and urgent message. The exhibition, named “Just a Dream,” a reference to a Jimmy Clanton and His Rockets’ song of the same name, challenges and comments on the conditions of contemporary American society. Through his work, Valdez urges viewers to find new paths forward by reflecting on the past.

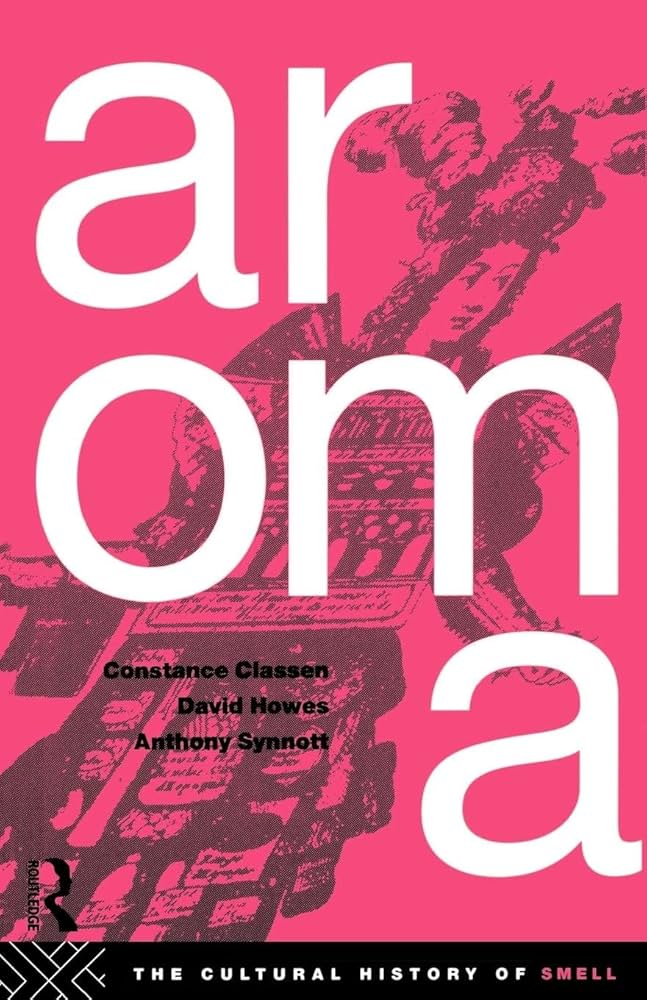

Valdez’s work speaks of his experience as a Chicano in the U.S. while taking influence from musicians, writers, activists, and fellow artists, such as Bob Dylan, Abel Meeropol, and Billie Holliday. Valdez uses these influences to further amplify his work and intersect his message with music and literature.

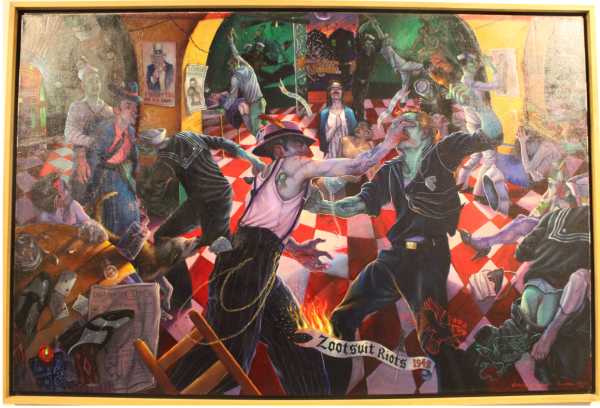

Even though Valdez is a Texas native, his works cross state lines to showcase injustices toward the Mexican American community. These include “Kill the Pachuco Bastard!” a fictionalized depiction of the Zoot Suit Riots in 1943, and “El Chavez Ravine,” a painting of the 1950s Chavez Ravine and the evolution of the Elysian Park community onto a 1953 lowrider ice cream truck.

Valdez’s artistic reach extends beyond regional and cultural boundaries. Through his connection between historical struggles and contemporary expressions of resistance, Valdez pays tribute to artists that have influenced him while engaging with social injustice, as seen in “The City I.”

“The City I”

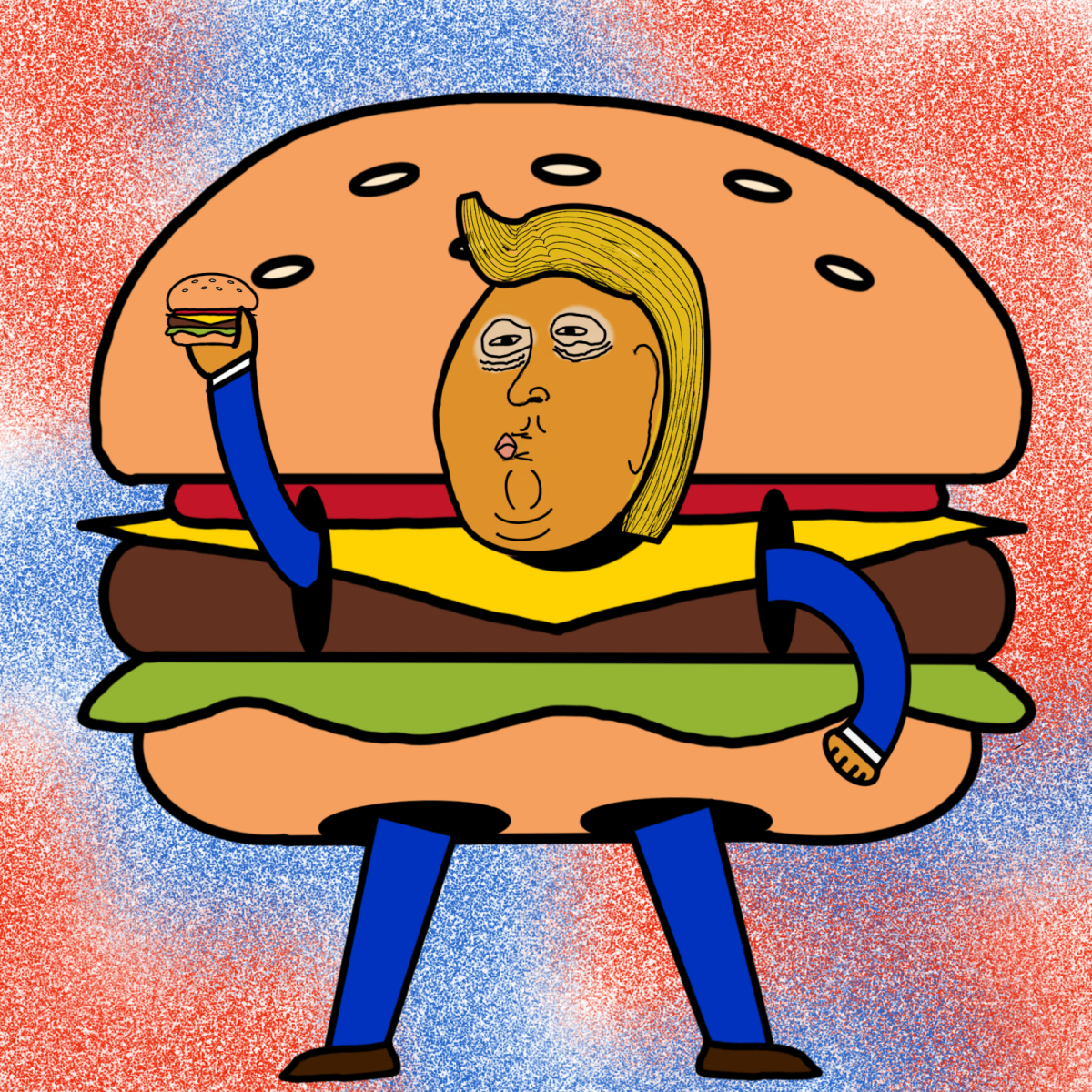

An homage to Philip Guston’s painting named “City Limits” (1969) and Gil Scott-Heron’s song “The Klan” (1980), “The City I” inserts Valdez among artists of different generations and demographics that oppose the Ku Klux Klan and have expressed so through their work. “The City I” references Valdez’s personal experience stumbling into a white power rally as a teenager and “City Limits”, which depicts three Ku Klux Klan members in a car with a city as a backdrop.

The usual reaction to “The City I” is one of deep dread, sorrow, remorse and astonishment at the sight of a 30-foot display of a symbol of white supremacy. Looking further, much like in City Limits, a modern city design can be seen, making the viewer confront the presence of overt racial hatred in contemporary society.

“The way that I like to read the work is that we’re so dumbfounded and shocked by the hooded figures that we forget that, actually, they are going back to that city without their hoods,” said Dr. Roberto Tejada, art historian and faculty at the University of Houston.

“They’re going to be the secretaries, the accountants, the police officers, the everyday citizens that make up the metropolis.”

During his discussion at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston with guest curator Terence Washington, Valdez references a lyric from “Killing in the Name” by the band Rage Against the Machine:

“Some of those that work forces

Are the same that burn crosses.”

The black and white color scheme leads viewers to believe that “The City I” is of a 1930s depiction of the KKK, but one of its most powerful details lies in the integration of modern items throughout the piece. A Klan member is casually checking their cellphone. The hooded toddler wears Air Jordan Nike shoes. A late model Chevrolet pickup truck is seen on the side.

While the name “The City I” certainly calls for viewers to confront extreme racial hatred that exists today, its name also has an allegorical meaning to how city designs are purposefully made to uphold and perpetuate that same hatred.

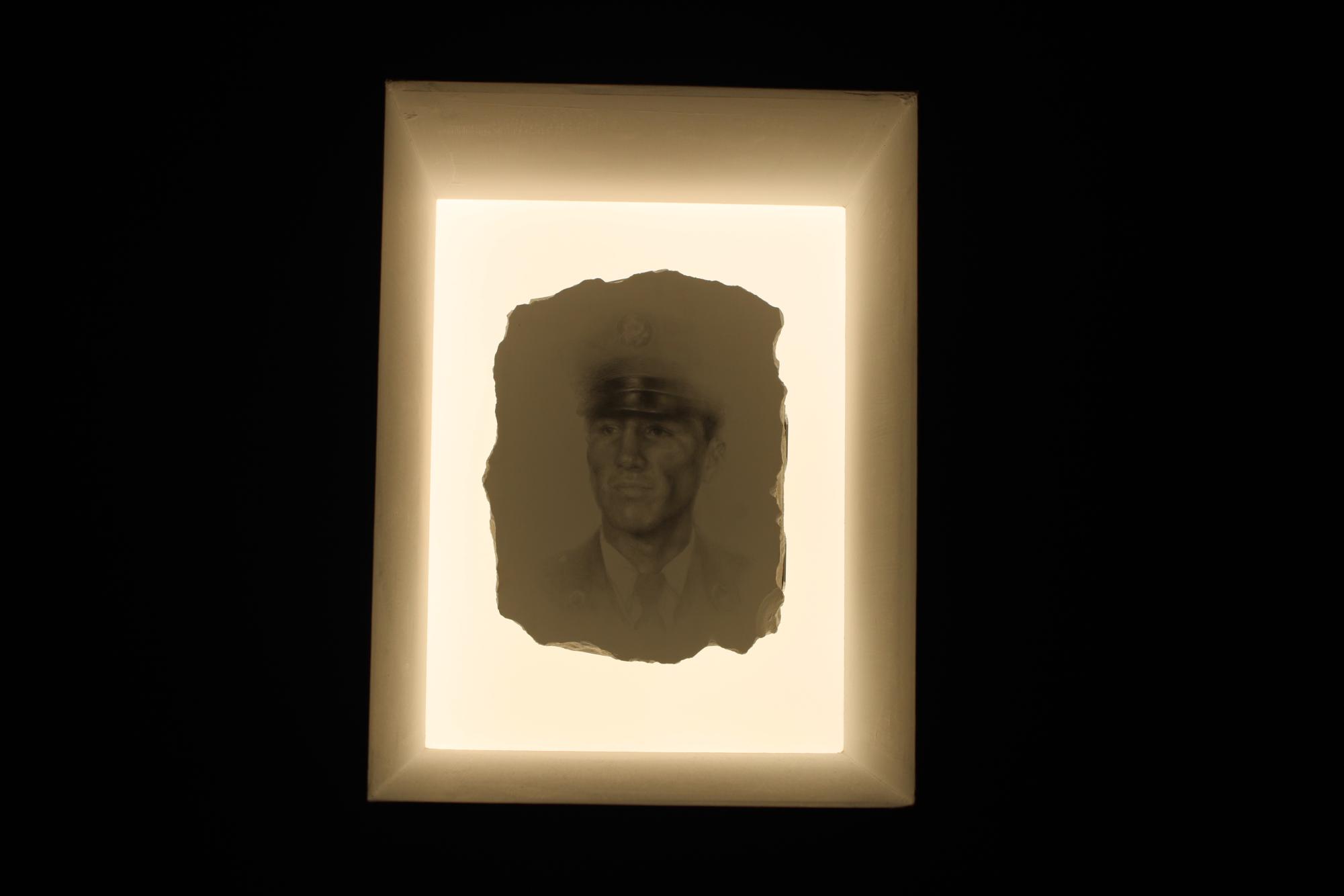

“Notes for a Future”

“Notes for a Future” is part of a memorial series honoring the life of José Campos Torres. Campos Torres, a Houstonian and military veteran, died at the hands of the Houston Police Department in 1977, the year Valdez was born.

His death led to a radicalization of the Chicano movement in Houston with multiple protests and the 1978 Moody Park Riot. After being arrested for disorderly conduct at a bar, three on-duty police officers beat him and took him to the city jail for booking.

His injuries were so severe that a supervisor ordered the officers to take Campos Torres to a hospital to get looked at. The officers refused the order and took Campos Torres to the Buffalo Bayou. Dr. Dwight Watson, author of “Race and the Houston Police Department, 1930–1990: Change Did Come,” describes the racially charged language officers used before Campos Torres’ final moments:

“As many as six to seven officers I believe ultimately come. And while there, they uncuff him and that’s when the last major fight occurs. Now mind you, José has been way past legally inebriated all day long, and at the end of the last fight that night, José Campos Torres is either pushed or falls into the Bayou. They say, ‘Swim across wetback, and if you make it to the other side, you’re free.’ Well, of course he didn’t. He drowned.”

For Valdez, history that is buried—the instances of discrimination and injustices that minorities in the United States face that often go unheard—are a subject of deep concern and a primary motivation for his artwork.

“I am alarmed by the denial of history,” Valdez said regarding “Just A Dream.” “Therefore, I create counter-images to defy our fateful desire to repeat history. I offer this work as a report—my visual testimony about a struggle for transformation, hope, love and survival in twenty-first century America,”

“Just a Dream” is on view at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston until March 23. Admission is always free.