Houstonians are rightfully proud of their multicultural history. The city is one of this country’s great cosmopolitan metropolises. Its global dimensions can overshadow its special, even crucial, place in the history of the North American borderlands.

I stumbled into the ambiguity surrounding Houston’s borderlands history one afternoon while teaching a course titled “History in Film.” Our unit focused on the history and cinema of the U.S.-Mexican borderlands, so I asked my students if they felt that Houston was part of the borderlands.

I was surprised (pleasantly so!) by the vigorous and wide-ranging debate that followed. They thoughtfully considered environmental, geographical, political, cultural, and historical factors, and they voiced thoughtful and nuanced arguments both for and against Houston’s place in the borderlands.

Most felt that cities like El Paso better reflected borderlands identity because of their desert vistas, proximity to Juarez, and connections to Southwestern culture and history.

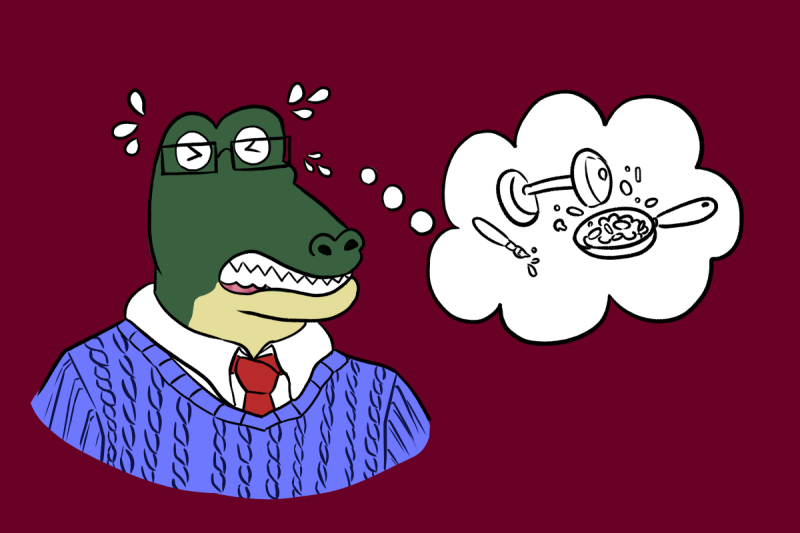

I agreed, at least initially. Having grown up in southern Arizona, I associated the borderlands with the Great Saguaro cactus, Gila monsters, and bone-dry weather punctuated by yearly monsoons, and not with lush bayous, alligators, and hurricanes.

It is crucial to appreciate Houston’s history as part of the Gulf Coastal borderlands because it is essential to understanding the struggles over culture and identity that are unfolding today. Let’s acknowledge this history, which may not be widely known among Houstonians.

In late October (or perhaps early November) of 1529, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and a handful of survivors from would-be Spanish conquistador Pánfilo de Narváez’s calamitous expedition, along what is now the United States’s Gulf Coast, landed on Galveston Island. Perhaps better put, a tempest belched the pitiful remnants of their flotilla, shivering, starving, and half-drowned onto the island’s southwestern tip.

The party, soon reduced to three Europeans and one enslaved person from Africa whose name was recorded as Estebaníco, was temporarily rescued from their dire situation by generous people living on the island. Cabeza de Vaca referred to the native tribe as the Capoque. The history of America’s southern borderlands began with this inauspicious meeting between representatives from three continents.

In the five years since he washed ashore on Galveston Island, Cabeza de Vaca and his fellow survivors made their way to the Rio Grande Valley, across the Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts, before eventually traveling south to the Valley of Mexico, where they once again reached lands dominated by the Spanish.

In short, the borderlands did not extend North from present-day Mexico to southeastern Texas, but rather from the Gulf Coast into the modern-day Southwest, before reconnecting with Spain’s American empire.

In the centuries that followed, the borderlands of the Gulf Coastline and the border waters of the Gulf Coast remained an important, multi-directional passage for people and their cultures. Before the U.S. Civil War, thousands of enslaved people fled south—including through Galveston—to Mexico, and sometimes settled in the country’s Gulf Coastal states, like Veracruz.

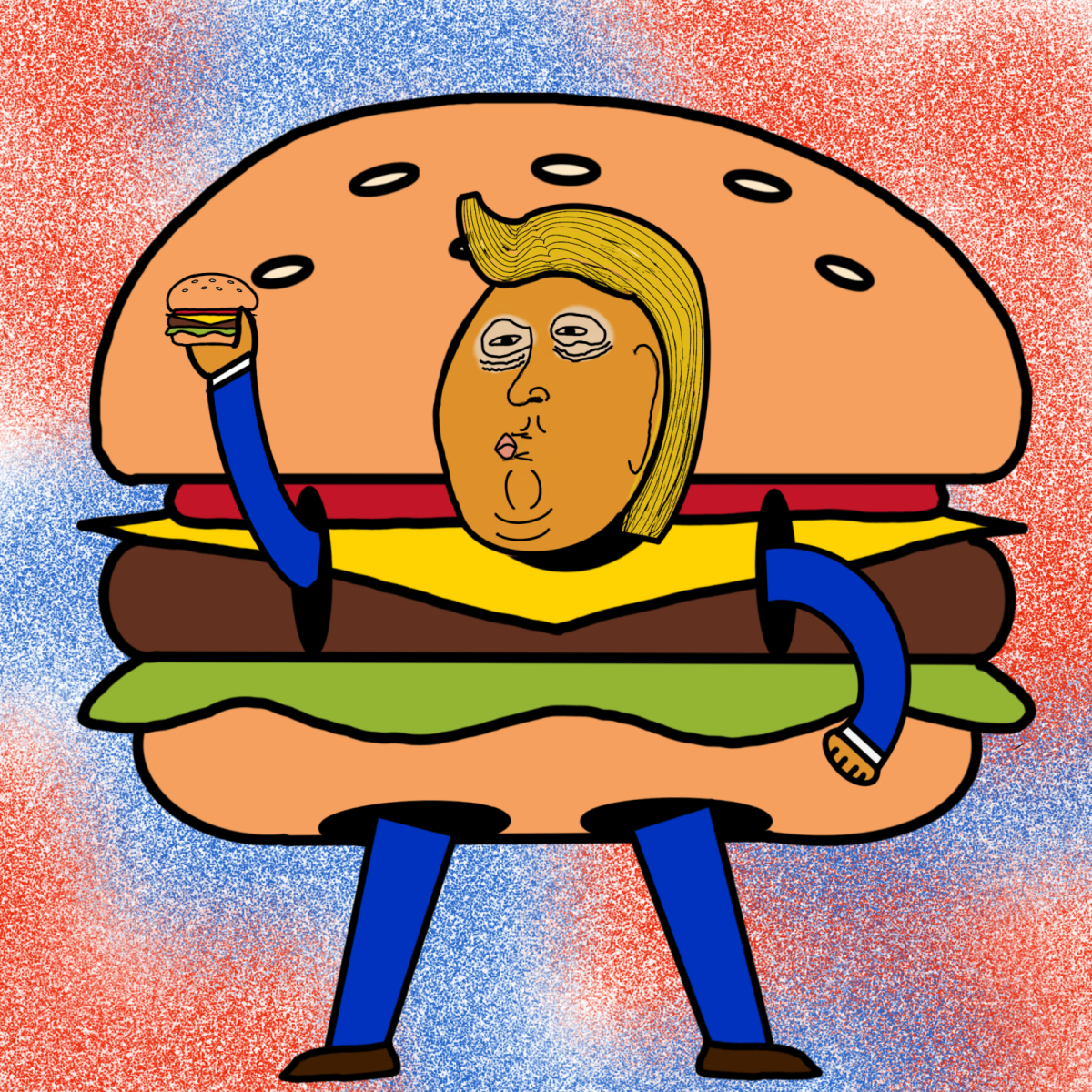

Today, attempts by Donald Trump’s second presidential administration to rebrand the Gulf as “America” amount to little more than the newest palimpsest to be slapped on top of 500 years of cultural and political history. After all, man-made borders (of any consequence) between the U.S. and Mexico didn’t appear in the region until the second half of the twentieth century.

From this vantage, the name change appears like a hackneyed attempt at erasing that history. It creates fodder for the culture war but lacks real geopolitical significance.

From another, it echoes the jingoistic rhetoric that preceded the U.S.-Mexican War. Contemporary critics of the war (like Abraham Lincoln) understood it to be an opportunistic and largely unprovoked land-grab, informed by the essentially irrational faith in Manifest Destiny.

It also resolidified the institution of slavery in a region where the practice was, until recently, under threat from the abolitionist government in Mexico City. After the war was over and the border was redrawn, many families whose lands and rights should have been protected by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo were left disposed.

Houstonians have every right to be proud of their borderland’s history, and we should do more to explore it. Studying it is crucial to understanding our historical and modern cultural identities. Preserving it is part of honoring regional heritage.

The current political environment, which is hostile to nuanced and complex histories, generally, and tends to regard them as un-American, threatens this history. Community organizations, student groups, and public institutions–including the University of Houston-Downtown–have a duty to protect it.

Thankfully, UHD is stepping up. The Center for Latino Studies, for example, does amazing work (the Center hosted the Cinco de Mayo celebration on April 21 and the 2025 Latinx Symposium).

Also, the College for Humanities and Social Sciences has formed a committee to explore the creation of a new degree in Latin American and Latino Studies, on which I am proud to serve. This degree has the potential to open further avenues for the study of the borderlands in Houston.

Even still, there’s more to Houston’s borderlands history than linking Texas history to Latin American and Latine history, although those are certainly important parts of the puzzle. Highlighting connections to Africa, Asia, Europe, and the U.S. South are as much a part of the borderlands here as they are in Sonora or California.

Investing in borderlands history in Houston is neither frivolous nor a luxury. It’s a critical investment in ourselves and our communities. It’s about knowing who we are and where we’re going.

About the Guest Contributor

Dr. Peter Soland, Ph.D. is an assistant professor of history with the University of Houston-Downtown, and the author of the book “Mexican Icarus: Aviation and the Modernization of Mexican Identity” and other scholarly publications. He’s currently a Multi-Country Research Fellow with the Council of American Overseas Research Centers. Ph.D. is an assistant professor of history at the University of Houston-Downtown, and the author of the book “Mexican Icarus: Aviation and the Modernization of Mexican Identity” and other scholarly publications. He’s currently a Multi-Country Research Fellow with the Council of American Overseas Research Centers.