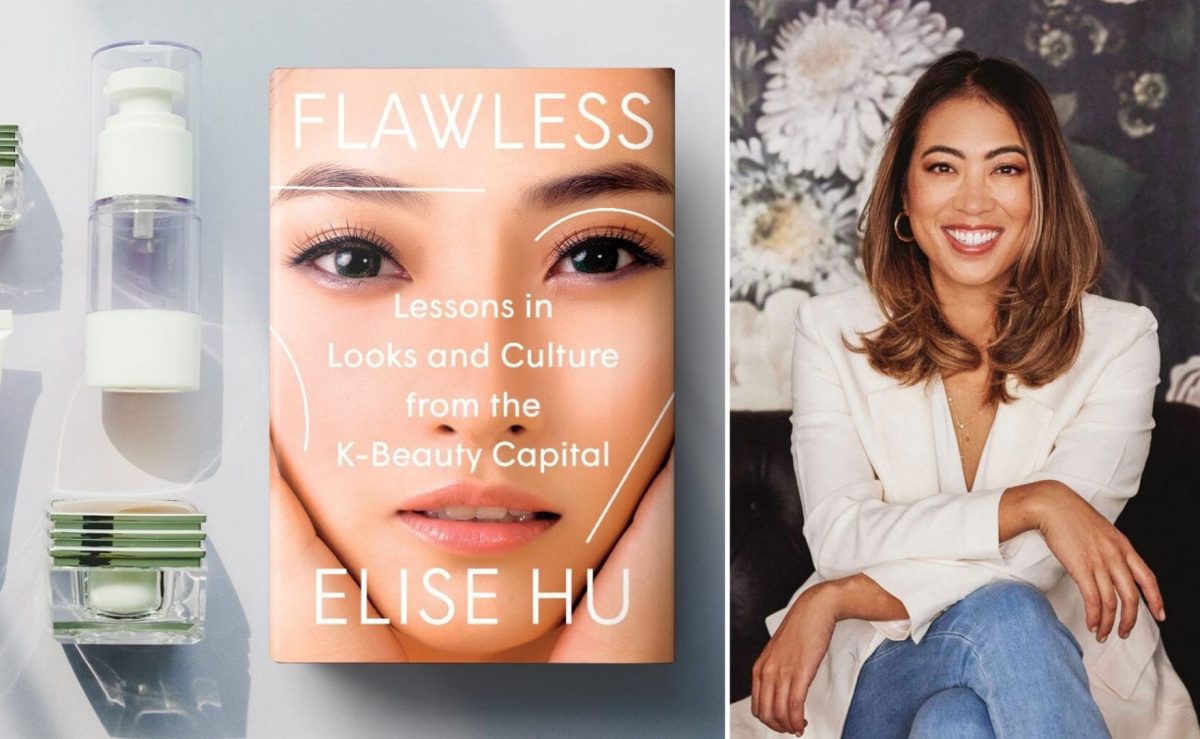

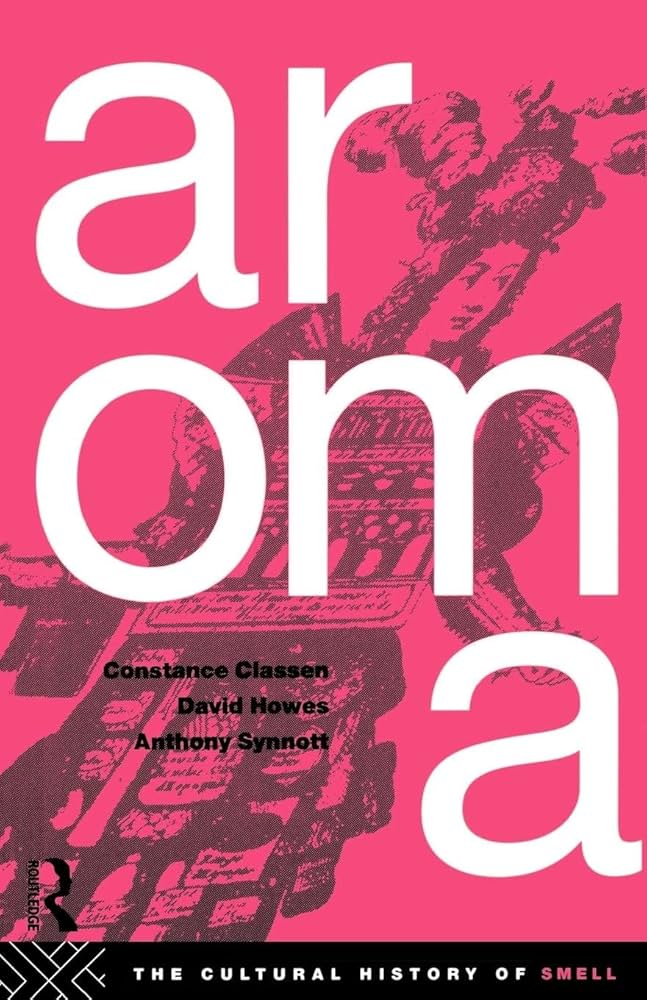

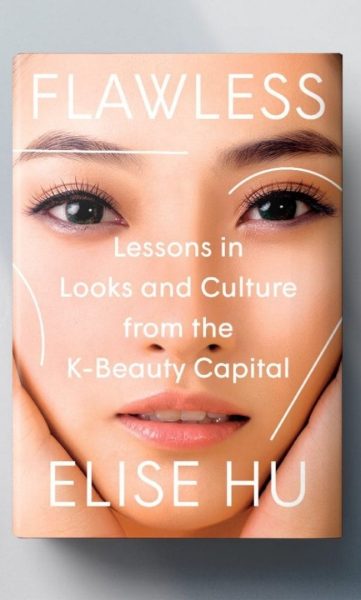

Seoul’s neon-lit streets, digital mirrors, and augmented reality filters are a focal point in “Flawless: Lessons in Looks and Culture from ,” where Elise Hu examines the interconnected techno-beauty aesthetic of South Korea.

Elise Hu, a journalist at National Public Radio (NPR), shares her experience living in South Korea as a Chinese American. She explores the urban landscapes to dissect the ways K-beauty reaches beyond skincare and makeup to a global philosophy of self-perfection.

“It is the world’s third-largest cosmetics and skincare exporter. South Korea is now exporting more in cosmetics than it exports in smartphones. South Korea may seem like it’s far away, a place that people aren’t going to visit, but it influences us and that’s why it’s not only an important place to be looking at but an important influence that shapes all of us,” remarked Hu in Boston’s NPR interview.

Hu’s book fuses personal narrative and rigorous reportage to question what happens when beauty becomes a cultural expectation and technological frontier. Her investigative reporting includes interviews with Korean survey participants, beauty executives, plastic surgeons, and influencers.

Blending memoir with journalism, Hu brings perspectives from philosophers and psychologists alongside her personal experiences to show that she’s not an outsider looking in, but someone immersed in the culture. Readers learn that beauty in South Korea is a form of labor, where looking good is rooted in Confucian philosophy, which emphasizes respecting the community through excellence.

Framing beauty as a moral virtue evolved alongside neoliberalism, where citizens became consumers through their ties to economic and social capital. Korean companies require headshots, height, and weight on résumés, while matchmaker services deduct points if one’s measurements do not align with a physical standard.

The consequences are translated into mass marketing of plastic surgery that dominates the Gangnam district, where people bring K-pop celebrities’ photos for reference. Western “wellness” culture and Korean influences demonstrate how self-optimization is becoming a global phenomenon.

Hu’s vision of the future depicts an urban façade populated by individuals who emulate augmented faces, filtered realities, and algorithmically enhanced beauty. When everyone achieves the same perfected look, does beauty lose its meaning? Or does it simply redefine itself through ever-narrower standards?

As humanity strives to accommodate its physical bodies, Hu’s book notes, “The kind of beauty we see in nature, or in art, shows us how beauty emerges from diversity and multitudes rather than sameness,” underscoring the importance of being unique.

K-beauty trends have spread rapidly with skin routines, “glass skin,” pimple patches, and AI-driven filters being exported globally. The transnational reach of beauty tech spans the Pacific, crossing from East Asian beauty industries to Western platforms like Instagram and TikTok, reinforcing each other. As we delve deeper into technological selfhood, conformity continues to distort authenticity.

The paradox of aestheticism will lead to a future cityscape where everyone will be glowing, symmetrical, and “optimized” — while those who can’t afford the upkeep will be looked down upon, enforcing classist values. Hu warns readers that the cost of perfectionism is an exchange of empathy and human longing that lies beneath the eclipse.

Perhaps beauty’s perfection isn’t freedom at all, but another kind of captivity — one willingly designed.